Why I Love Writing

I worked at ACT for almost 13 years, and in that time I read hundreds of thousands of student essays written in response to ACT Writing prompts my colleagues and I wrote. In the earlier days, I held them in my hands. By the time I left, I was reading them on screens, and some essays were typed.

The essays in published ACT practice books give me the feels—I read these as daily references

I treasured those essays. As a content specialist who developed exams, my work impacted potentially millions of students over the course of just a year. I wrote many of the words students would see, and think about, and possibly wrestle with, on some of the most important days of their educational journeys. But I rarely saw and interacted with students directly.

So I read their essays. As the cliché goes, they made me laugh, they made me cry, they made me angry, they made me hopeful. I learned new words (I’m so old that I literally learned “YOLO” from student essays!), fresh perspectives on important issues of the day, stories from the everyday lives of students, heartwarming and heartbreaking messages from kids in the US and overseas.

Why were these essays so important to me, beyond how they interfaced with our rubric?

Because at its most basic, foundational core, writing is connection.

The most basic, foundational core of my values and the way I move through the world is connection. To me, being human is about reaching out and touching what is around me—the cat who is about to walk across my keyboard, the wind that whooshes in that singular way as it moves through a pine grove, the strangers who smiled at me as I walked to an engagement this morning. Connecting with something or someone outside of ourselves, touching the world around us, gives us proof that we are here, that we exist, that we are alive. Any computer can think, but it takes a human being to connect. I touch, therefore I am.

Until relatively recently in human history, people communicated through spoken language. You spoke to no one farther away than you could throw your voice. Spoken language has strict limits in terms of time and space; once the message is uttered, it’s gone.

Writing was, and probably still is, the most revolutionary development in human technology. Once words (or early symbols) go from your mouth or your mind to a stone wall, a piece of parchment, or now a phone screen, they are breaking the bounds of space and time. Think about how incredible that is. If you have a group of monks or a printing press to copy those words, even the physical erosion of written words can be forestalled indefinitely. We talk all the time about how we can store vast amounts of knowledge now, and how we need less memory capacity in our noggins, but what excites me the most is the potential of writing to form, strengthen, and maintain human connection across time and space. There is no one to which we cannot be connected if we can access their writing, they can access ours, or both.

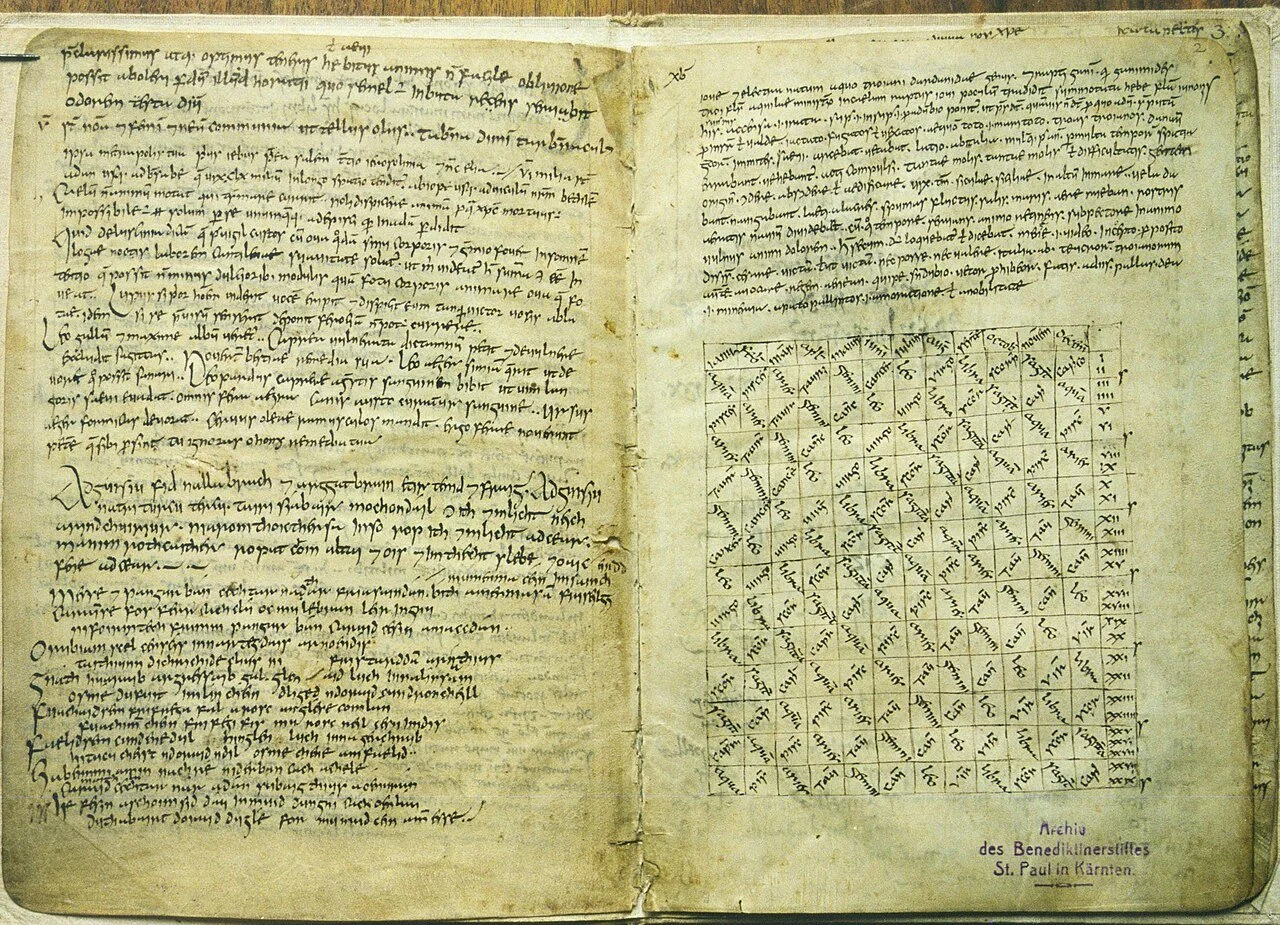

From the page on which the 9th-century poem “Pangur Bán,” written by an anonymous monk in Old Irish. Writers with cats who walk across their keyboards love it, and it is proof cats have been interrupting our work for centuries! An excerpt from the translation by Robin Flower: “I and Pangur Bán, my cat, / 'Tis a like task we are at; / Hunting mice is his delight, / Hunting words I sit all night.”

And there is no limit to the kinds of connections we can make through writing. Shakespeare’s plays can warn us, 21st-century people, about the consequences of abuses of power. Wendell Barry’s essays can, as they have for me, teach us new and deeper ways to learn from nature. A poem we send out into the world can find the person who finally reads words in the exact shape of their experiences, and feels affirmed. We transmit knowledge, history, wisdom, values, warnings and lessons hard won through writing. And even if you sit alone in, say, an attic for years on end, as did Emily Dickinson, writing is the way you touch the world. You can never be truly alone if you have a book to read or a pen and paper to write. One of Dickinson’s most loved poems, one I know by heart, is about the ability of writing to connect us to places and times to which we’d otherwise have no access:

There is no frigate like a book

Nor any coursers like a page

Of prancing poetry

This traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of toll

How frugal is the chariot

That bears the human soul!

So . . . what does this all have to do with you? You might be here because you or your child is struggling with writing. You might be thinking of writing as a difficult task you are forced to undertake because of the rules of the world and education. I believe you. Writing can be so, so, hard. But lots of things that are hard pay dividends many times over, and such is the case with writing. Instead of thinking of your next assignment as a hurdle to get over on your way to the next class, try on the idea of your assignment as a form of connection with your teacher (or even your future self! It’s fun to go back and see how you thought about the world when you were younger). What might that release for you? Could it possibly free something inside of you that’s been trying to make its way out?

Who are you in the world, and what words will you leave here for the future? Let’s find out.

Let me help you draw out the words that have been yearning to get onto the page.